One of the most critical issues in the development of petrochemistry is the provision of skilled personnel. Without it, all efforts to “boost” the industry might fail.

Recently, Kazakhstan hosted two major international forums focusing on new capital projects in the extraction, transportation, storage, and processing of oil and gas—the “ENERGY TRENDS: Gas & Petrochemicals” conference and the XI Annual Conference “Kazneftegazservice-2023: Oil and Gas Construction and Engineering.”

A recurring theme across most of the presentations was that oil and gas, which currently form the foundation of the national economy and generate substantial export revenue, could have even greater value if processed domestically. Consequently, the government faces a strategic task: to establish a petrochemical industry.

But how can this goal be achieved without ensuring the industry has the necessary personnel in sufficient numbers? This is the key issue—discussing the number of specialists entering the industry through the education system and the quality of their training.

The projects already underway and those being announced in the industry require a significant number of specialists in chemistry, engineers, and mid-level technical personnel. However, data show a year-on-year decline in the number of graduates in chemical specialties. The government allocates more and more grants for these specialties, yet a substantial portion remains unclaimed by applicants, and not all students make it to graduation. Why is the attractiveness of chemical specialties declining? Two reasons explain this trend.

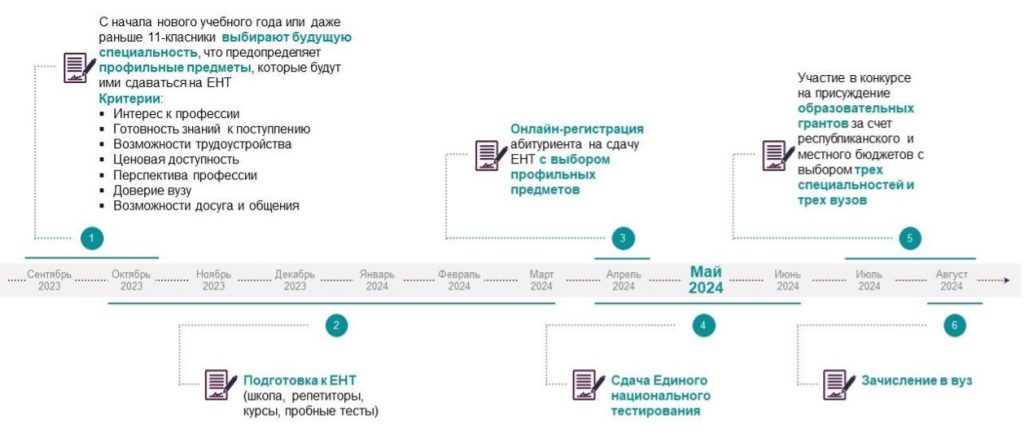

First, applicants are simply afraid of the entrance exams required during the Unified National Testing (UNT) phase. To enroll in chemical specialties, candidates must take two core subjects—chemistry and physics. Both are technical and very challenging. According to our estimates, only about 0.5% of all UNT takers choose this pair of core subjects. In comparison, nearly one-third of applicants opt for mathematics and physics, while about one-fifth choose chemistry and biology.

Previously, applicants pursuing chemical specialties needed to take chemistry and biology, which kept the number of applicants and students relatively stable. However, after the Ministry of Education and Science replaced the core subject pair with chemistry and physics, a downward trend began to emerge.

On one hand, the ministry’s decision can be justified since, in other countries—particularly those with well-developed petrochemical industries—this specific pair of core subjects is standard for chemical specialties. On the other hand, chemistry/biology combinations are also widely used abroad. Therefore, we believe it is worth revisiting the idea of reverting to the chemistry/biology combination, given Kazakhstan’s unique circumstances.

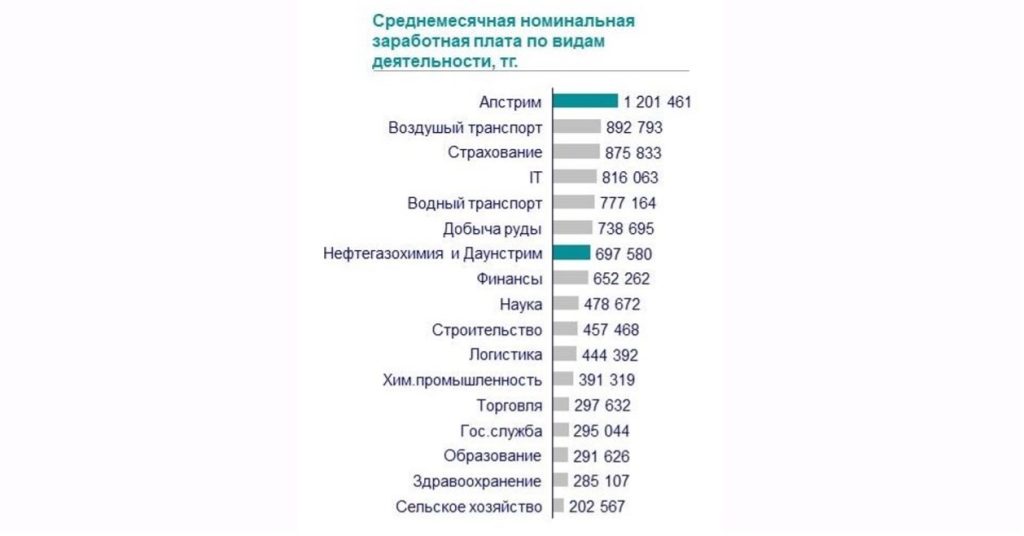

Average Monthly Nominal Salary by Industry, KZT

The second reason for the declining number of applicants is, of course, salary levels. The average salary in petrochemistry and oil and gas processing does not exceed 700,000 KZT. For the Kazakhstani labor market, this is a decent level, but it is still lower than in many other sectors. For example, there is a significant gap compared to the average salary in oil and gas extraction, which is 1,200,000 KZT. Salaries in the fields of air transportation, insurance, and information technology exceed 800,000 KZT. It is clear that talented and ambitious applicants are more likely to choose higher-paying professions than those in petrochemistry and downstream industries.

Note: Upstream refers to oil and gas exploration and extraction, midstream to storage and transportation, and downstream to processing and distribution of end products.

Now let’s move from quantity to quality. The quality of education depends on its content. High-quality education can only be ensured by maintaining high standards at every stage of the content creation chain. This chain includes the development of professional standards, the creation of educational programs based on these standards, and further programs to ensure qualified engineering and teaching staff. It also involves creating a strong material and technical training base and a comprehensive educational and methodological framework, which includes textbooks, training materials, test assignments, and more.

There are challenges at every stage.

For example, since professional standards serve as the technical specification, reflecting all the knowledge and skill requirements for future specialists, their development should be handled by industry professionals. However, discussions with industry representatives and the education system reveal that this work is often quite formal and lacks efficiency. The industry specialists responsible for this task are usually current employees who do not have enough time to focus on developing professional standards without being distracted by their daily duties. Moreover, they often lack the necessary expertise in standards development because they are not adequately trained for it. As a result, education system employees often draft the professional standards, with industry professionals only making minimal adjustments.

As for educational programs, until recently, the key program for petrochemical production was chemical technology of organic substances. However, industry representatives note that this program is not fully suitable, for instance, for polymer production, aromatics, and their derivatives. Yet this is exactly the type of production that will dominate the industry in Kazakhstan over the next decade.

Furthermore, the programs often lack sufficient emphasis on practical training. Efforts to improve material and technical resources are constrained by financial limitations. There is also a shortage of engineering and teaching staff due to the underdevelopment of the industry as a whole.

If we summarize all the issues in workforce training for petrochemistry, it can be expressed as follows: the number of students in a field losing its appeal is decreasing, and they are being trained using programs that are neither suitable nor of sufficient quality.

What Needs to Be Done?

The answer lies in at least three areas.

First, it is evident that the country’s education system must respond to the new demand from the industry. Currently, about 25 universities and up to 40 colleges train specialists in chemical fields. However, in the context of Kazakhstan’s labor market, even technical plant operators will require higher education rather than just technical secondary education. Therefore, the primary focus should be on university-level training.

Comparison of Universities by Graduate Salaries, Employment Rates, and Job Search Duration (on Average)

Here, we divide universities into two groups.

The first group includes leading universities in Almaty and Astana: Kazakh-British Technical University (KBTU), Satbayev University (Kazakh National Technical University named after K.I. Satpayev), Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, and Nazarbayev University.

The second group consists of regional universities: Safiy Utebayev Atyrau Oil and Gas University, Toraighyrov University in Pavlodar, and Mukhtar Auezov South Kazakhstan University in Shymkent.

The key question is: with which universities should partnerships be established for workforce training?

Universities in Pavlodar and Shymkent maintain strong ties with local employers, primarily regional oil refineries. For instance, the Pavlodar Oil Chemistry Refinery is essentially the backbone of the city’s economy, so graduates of Toraighyrov University face no issues with employment.

In the southern regions, income levels are traditionally lower than in the northern regions, but the cost of living is also lower. This makes employment at the Shymkent Oil Refinery an attractive option for graduates of Auezov University.

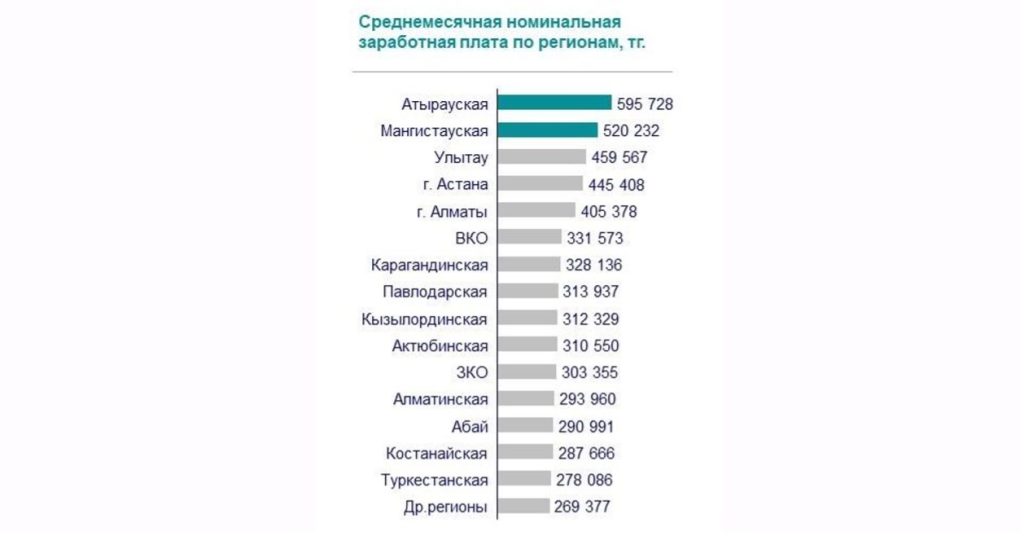

Average Monthly Nominal Salary by Region, KZT

The situation with Atyrau Oil and Gas University is more complex. In the Atyrau region, the average salary is approximately 600,000 KZT, the highest in the country. However, salaries in oil refining and petrochemistry may not be competitive compared to other employment opportunities in the region.

This is evident from the fact that workers from almost all oil extraction companies in the region strive to secure jobs at Tengizchevroil and North Caspian Operating Company, as these companies offer significantly better working conditions and higher pay.

Considering that most new petrochemical facilities are planned for western Kazakhstan, the issue of staffing for these industries will persist in the region due to relatively low wages.

Another challenge is that most parents prefer their children not to study in Atyrau. Additionally, Unified National Testing (UNT) results from local schools show that applicants to Atyrau Oil and Gas University often have a lower level of preparation compared to those entering top universities in Almaty.

Therefore, workforce training for petrochemistry in Kazakhstan should be centered around universities in Almaty and, to some extent, Astana, as these institutions are the most active in updating educational content and collaborating with employers.

However, this raises another issue: how to attract graduates from these universities to work in the western regions of the country.

The solution lies in the second essential condition: raising the level of pay in petrochemistry. This is a challenging, complex, but absolutely necessary task. In addition to higher salaries, it is also crucial to ensure attractive working conditions.

For example, petrochemical facilities often operate on fixed-shift schedules, requiring workers to stay permanently in Atyrau. Transitioning to a rotational work schedule would allow employers to broaden their geographic search and attract qualified personnel from across Kazakhstan and even from neighboring and distant countries.

Only through high salaries and comfortable working conditions can applicants be attracted to chemical specialties. Considering that many teenagers choose their future profession before finishing school, it is logical that promoting careers in the petrochemical industry should start as early as the 10th or even 9th grade.

To ensure that career guidance initiatives are effective, they must be diverse in both form and content, rather than limited to job fairs and university presentations.